Scholars of public history and national memory tell us that monuments are arenas for competing historical narratives. Public monuments, mausoleums, museums, galleries, exhibitions, street names and names of buildings are all trophies belonging to the winning teams in history. They do not and perhaps cannot record an all-encompassing history, but only the specific version of history that is authorised by the winners. Every narrative has its narrator, and public history is the story of the hunter; lions seldom write the scripts that are enacted on the stages of national monuments and museums. Of course, heads, skins and claws of lions often line the walls where hunters live. But this display should never be mistaken for co-authorship. It is still the hunter who decides which parts are to be displayed, where, when and for how long.

Scholars of public history and national memory tell us that monuments are arenas for competing historical narratives. Public monuments, mausoleums, museums, galleries, exhibitions, street names and names of buildings are all trophies belonging to the winning teams in history. They do not and perhaps cannot record an all-encompassing history, but only the specific version of history that is authorised by the winners. Every narrative has its narrator, and public history is the story of the hunter; lions seldom write the scripts that are enacted on the stages of national monuments and museums. Of course, heads, skins and claws of lions often line the walls where hunters live. But this display should never be mistaken for co-authorship. It is still the hunter who decides which parts are to be displayed, where, when and for how long.

It is within such a critical framework that we need to discuss the new Mau Mau monument launched by the UK government at Uhuru Park’s Freedom Corner, in downtown Nairobi, last Saturday. The monument is the “final instalment” in the 2013 out-of-court settlement for Mau Mau veterans who suffered torture and illegal detainment in the hands of colonial officials during the infamous State of Emergency, 1952-60. Crafting “special” emergency regulations in order to quash the Mau Mau insurgency, the colonial state in Kenya backed by British troops specially deployed in response to the insurgency, incarcerated tens of thousands of Mau Mau suspects, often without charges, and inflicted brutal torture on them.

Underneath the surface of the out-of-court settlement that was announced in June 2013, lies a deep history of denial and evasion by the UK government. Since the achievement of Kenya’s independence in 1963, the British government had refused to take responsibility for the brutal torture and illegal detainment of Mau Mau suspects, on grounds that independence meant Kenyatta’s government had inherited Britain’s legal responsibilities in Kenya. This diversionary tactic ensured that for more than half a century, the UK government did not pay any kind of compensation to Mau Mau veterans. But all this changed in October 2012 when the London High Court, in a case brought before it by the Kenya Human Rights Commission, ruled that there was sufficient evidence to sue the British government for crimes committed against Mau Mau suspects during the struggle for Kenya’s independence. Fearing that this landmark ruling would result in hundreds and possibly thousands of individual Mau Mau litigations being brought against it, the UK government quickly opted for an out-of-court settlement with the Mau Mau War Veterans Association. The settlement agreed upon was £19.9m that has already been paid to the veterans, though some claim to not have received their share, and the Mau Mau monument that was launched last Saturday.

The carefully-worded epigraph on the new monument betrays this long history of denial and the politics surrounding the memory of Mau Mau. It reads, “Memorial to the victims of torture and ill-treatment during the colonial era.” The ambiguity of the epigraph is not accidental; inconvenient truths such as who authorised and conducted the torture, who the victims were, and why they were tortured are omitted deliberately. This intentional vagueness was similarly used when William Hague, Britain’s Foreign Secretary, announced the settlement before the British parliament in June 2013. Rather than offering an official apology, Hague noted that the British government “sincerely regretted” what had transpired in late colonial Kenya. And so just like in the epigraph on the new monument, the British government again refused to accept liability in its official statement announcing the settlement.

It is therefore hypocritical of the British High Commissioner to Kenya, Dr. Chris Turner, to talk about the significance of the monument in reconciling the British government with her Kenyan counterpart, and with Mau Mau veterans. The foundations of such a reconciliation project can only be laid with a genuine admission of liability and a sincere apology by the British government. To be sure, no amount of money or number of monuments can fully compensate Mau Mau veterans for the beatings, castrations, rapes and trauma experienced during the anti-colonial struggle. But a forthright statement of apology, devoid of clever wording and evasiveness, can serve as a soothing balm for their festered and decades-old wounds.

In conclusion, Kenyans too have a role to play in the quest to compensate Mau Mau veterans. The Kenyan government, for example, has promised for years to provide free social services to Mau Mau veterans, but this has never been realised. In addition, justice for Mau Mau veterans must go hand in hand with justice for the history of the Mau Mau movement. Kenyans must play an active role in the collection and preservation of not just Mau Mau history, but Kenya’s colonial history in general, as this generation of Kenyans who lived through colonialism continues to diminish rapidly. Scholars, journalists, religious organisations, artistes and musicians all have a part to play in pursuing this kind of collective justice. Only then can the lions truly tell their tales.

By Muoki Mbunga

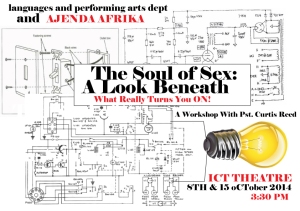

On October 8th 2014 at Daystar University, Athi River campus, Brother Curtis led us in the discussion of the thoughts he had

On October 8th 2014 at Daystar University, Athi River campus, Brother Curtis led us in the discussion of the thoughts he had